Remembrance Sunday is an occasion which, for many of us in the UK and other countries, is at once at a national event and a deeply personal one. In the two minutes of silence whereby we mark the service of previous generations, it is natural to focus on one’s family and how the conflicts of the twentieth century affected close relatives. I always think about my two great-great-uncles who were killed in action during the First World War, William Henry Dixon and Arthur George Childs. William Dixon is commemorated on the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium, and Arthur Childs is buried in the French village of Outtersteene. Recently, a relative of mine showed me a letter sent by my great-grandfather Charles William Dixon (brother of William Henry Dixon), an electrical engineer employed by the Royal Navy during the war, to his brother-in-law Arthur George Childs. It is poignant because, unbeknownst to my great-grandfather, Arthur was dead by the time the letter was written, and it was returned to the sender. I have transcribed this and am publishing it here as a small memorial to the generation who fought in the First World War and their sacrifices. Charles Dixon was much more fortunate, living until 1967.

L-R: William Henry Dixon (1891-1915), William Dixon (1855-1945) and Charles William Dixon (1886-1967).

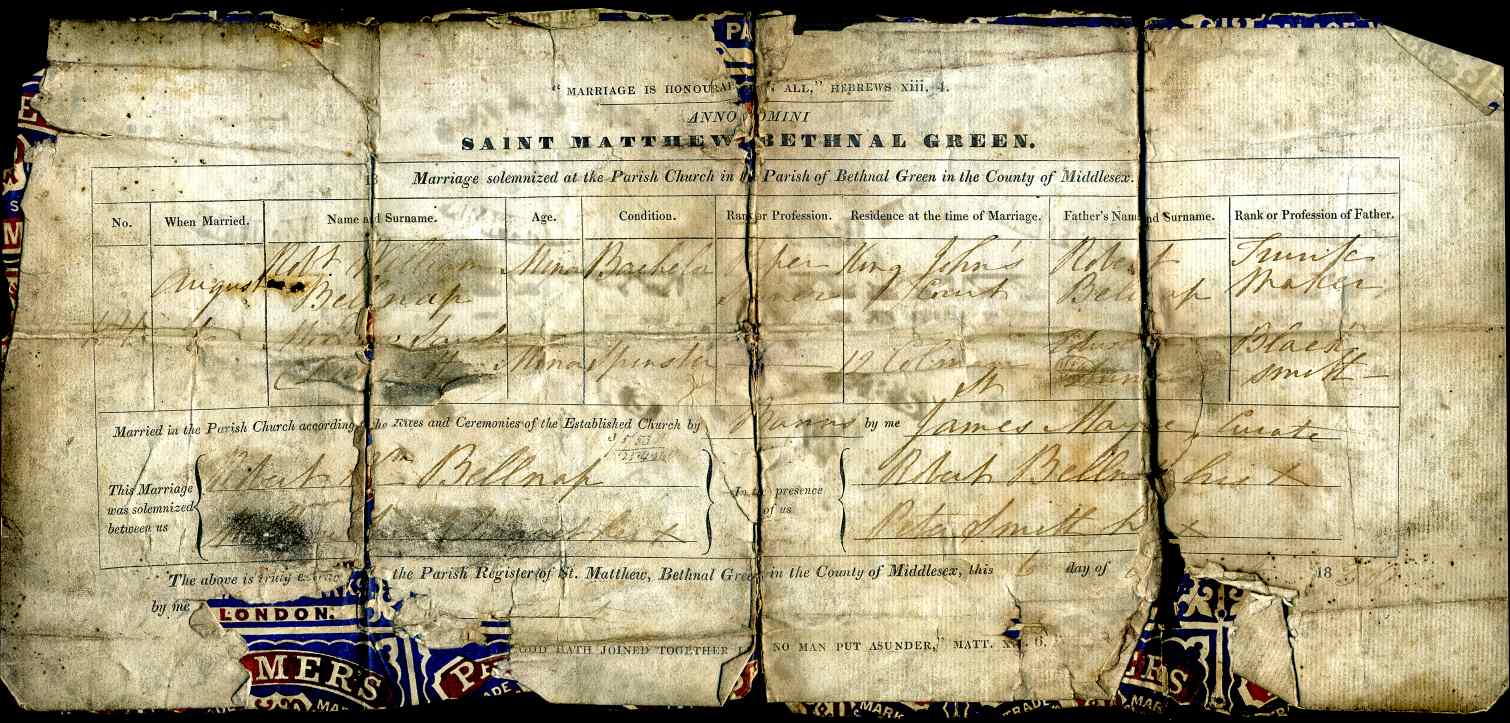

Charles William Dixon to Arthur George Childs, 30 April 1918

H.M.S. Victorious Mess 52,

Tuesday April 30th 18.

Dear old Arthur

I am afraid that while I have been on leave I have entirely forgotten you old man, but although I have not sent along we have always been talking of you and wondering how you were getting on. We have a good idea as to where you are and so when we follow up the news in the papers can form a rough idea as to what you are up to. I guess you are saying that it is a rough idea and I suppose it is, for unless a chap has been through it he can form no true opinion on the matter. I was glad to learn that you well [sic] on reaching home, and so are all at home when the news is passed round that Annie has heard from you. I had a very comfortable ten days at home old boy and wished you were lucky enough to get the same. I saw Annie several times and she looks well. It is only natural that she should be anxious on your account but the spirit of fortitude the lasses show is astonishing. You can bet that I did not relish the return journey very much neither did Bertha. The worst part of any leave is the return and it comes along with wonderful speed I can assure you. However I made the most of the time. We had a children’s party on the Saturday evening as no doubt Annie has already told you. Percy & Minnie turned up to our great surprise and delight also Aunt Bertha. Things went very merrily but the beer was limited to three small bottles of Savills between three thirsty chaps. However we overcame that trouble by the aid of a bottle or two of whisky and finished up in very high spirits. We only wanted your company to make the thing complete. Jack acted the role of comic singer, but of course his stock of comics is rather limited and many was the time I wish you could have dropped in to oblige. Mind you had you done so the whisky’s life would have been considerably shortened but we would not mind that much. When are you to have your leave old chap, but I don’t suppose you get any idea as to when that will be. I would do anything to see you when you do come up. I missed Will this time by a matter of days and was sorry to do so, have not run across him now for ages, last time was before he was married. What a gathering it will be when we all do meet. Think we will make an all night of it, what say you. Jack went up again while I was home and they have once again sent him back to his work. He is not grumbling and I don’t blame him. It cannot be very comfortable out there. Still the people who pull the strings are just as sleek as ever, and were we to know half the things being done our hair would stand up. You will be pleased to know that I found Bertha and the little ones well. In fact I might say remarkably so. The kiddies converted me into as big a one as themselves, as per usual, and I can assure you we had a good time. The weather was nothing extra but being a homer that did not worry me much. I could not help smiling when Annie told me of your new hobby, it must be wretched old chap to have so many live stock about you. I suppose it is impossible to overcome them as they are so numerous. It does not bear thinking about. Let’s hope that the end is not far distant. I cannot see it yet however, although at times I think it will finish as quickly as it began let’s hope so at any rate. What do you boys think of the Navy’s latest achievement. Almost takes your breath away to think they had such cheek, a bit of the Nelson touch. Eh. Of course the people in the Navy realise that what they did is only what you chaps are doing every day, don’t forget that, but it is a bit of a novelty to some of our chaps and so they are deservingly proud of it. I am sending along a tin of the best tomorrow hope you will get it safely. Best of luck and good wishes and a speedy return.

Your affectionate brother

Charlie

Arthur George Childs (1888-1918) with his wife Annie.

To assist readers to understand the above letter, I am giving a little more context. Charles William Dixon was born in West Ham, Essex (now in Greater London), in 1886. The eldest son of a ship’s cook, he trained as an electrical engineer and moved to West London, working at the Great White City, where massive exhibitions were held prior to the war. In 1909, he married Bertha Ada Childs. Arthur Childs, the recipient of the letter, was one of Bertha's brothers. He was a furniture salesman and a private in the Machine Gun Corps. His wife was Annie Elizabeth Perry, whom he married in 1911. Another brother, also mentioned in the letter, was Percy John Childs, who married Miriam (Minnie) Willson in 1910. William Charles Childs, also a brother of Bertha, was a merchant seaman who married Caroline Twigg in 1916. One of their sisters, Edith Alice Childs, was married to John Herbert (Jack) Finch, a postman, in 1907. One of their maternal aunts, Bertha Annie Maggs, is mentioned too. Charles William Dixon was a freemason from 1912 to 1923, and the register of his masonic lodge in Hammersmith records that he was away on war service from 1915 to 1918. He was not demobilised by the Admiralty until 1919. HMS Victorious was a repair ship stationed at Scapa Flow, where Charles later recalled being a witness to the scuttling of the German fleet after the war. The naval action to which he alludes towards the end of the letter is the Zeebrugge raid of 23 April 1918, in which the Royal Navy attempted to block an occupied port in Belgium. The British press reported this raid as a great triumph, although it was largely unsuccessful. The conflict continued until 11 November 1918.