Reflections on the Coronation

Having written something about the role of the Church of England in my family history, this month seems an appropriate time to write something about the role of the British monarchy.

I have lived with the coronation, maybe more than most, for the past decade. In 2013, I began researching coronations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries while I was a history student at Oxford and needed to write a dissertation. This experience was highly formative, and laid the foundation for all my subsequent historical research as an MPhil then as a PhD student. Recently, I have had two analyses of coronations published (see my publications). My work on this subject was for a very brief time highly topical when it was publicised in the run-up to the coronation of 2023 (including in the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and a House of Commons Library research briefing). In the week of the coronation, I gave an online talk for the Society of Genealogists about how to trace members of the Royal Household and other links to the monarchy.

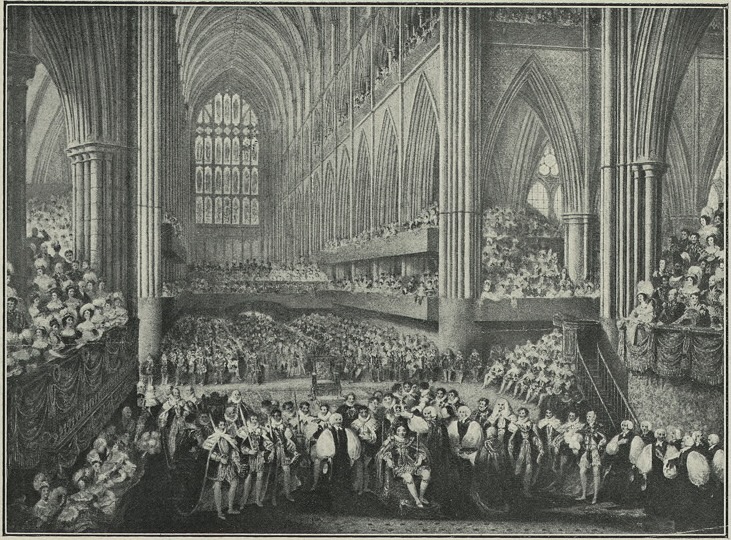

The prospect that there would be a coronation before long has also been a part of my life, though I dreaded the death of the late Queen while she was still alive. Last year I stood in the crowd in the Mall to witness her solemn cortege passing by before the lying-in-state at Westminster Hall, aware that I was witnessing a unique moment in history I would never forget. And when the coronation came earlier this month, I was transfixed by its numinous quality. It is one thing to write about coronations, another to witness them. When the historical novelist Walter Scott attended the coronation of King George IV in 1821, he was seen ‘in great ecstasies and half beside himself with delight and admiration at the show’.

The coronation of King George IV in 1821.

Source: New York Public Library

Such feelings are very distant from my detached historical approach, which has sought to discuss the religious dimension of monarchy in an analytical fashion. However, genealogy has helped me to understand a longer chain of events, long predating my personal historical interest in the monarchy, which have affected the way that I view the monarchy and the effect that it has on me. I am acutely aware that I have London ancestors, some of whom have lived in and around the metropolis since at least the time of George III’s coronation. And I have inherited and acquired many objects that relate to previous royal occasions. So I see the latest coronation as a continuation of something with deep and unfathomable roots.

My 6x great-grandfather, Alexander Wood, was baptised at St Mary, Whitechapel on 18 September 1761, four days before the coronation of King George III and Queen Charlotte. His family lived in Goodman’s Yard, very close to the Tower of London. They would no doubt have heard the guns fired from the Tower and the ships anchored in the Thames at the moment of the King’s crowning. Boisterous behaviour followed this moment in the streets of London.

An engraving of London from the topographical collection of King George III.

Source: https://flic.kr/p/2jzH6M6

Alexander Wood did not live to witness a coronation as an adult. He was buried on 4 July 1820, a few months after the death of George III but a year before King George IV’s coronation. On 4 July 1821, in the month of the coronation, my 4x great-grandfather Henry Thomas Bridge was born in Marylebone. The Bridge family were living in Hertford Street (now Whitfield Street), by the time of his baptism. Another ancestor of mine, my 5x great-grandfather William Henry Timms, was picture framer to Sir Thomas Lawrence, who painted the coronation portrait of George IV. Timms was an erstwhile resident of Marylebone.

My 4x great-aunt Elizabeth Flowerday was born in the year of George IV’s death and baptised at St Mary, Whitechapel, in the year of King William IV and Queen Adelaide’s coronation. Elizabeth lived until 1919, long enough to bequeath in her will some money from her Post Office bank book to her nephew James Thomas Flowerday (my 3x great-grandfather), giving his address as the house in which my paternal grandmother was born five years later. Elizabeth died in Alfred Place West, Kensington, where she had long been a servant in the household of one of Queen Victoria’s physicians. In 1838, the year of Victoria’s coronation, my 3x great-grandmother Christiana Catton had also been a servant in Kensington, at Pelham Crescent. It was at Kensington Palace that Queen Victoria had spent her childhood.

Elizabeth’s brother James Flowerday, my 4x great-grandfather, was a colour sergeant in the 3rd City of London Rifle Volunteer Corps, and is recorded in a newspaper parading before the future King Edward VII at Wimbledon Common in 1868. It is probably from his side of my family that we have a mug commemorating Edward VII’s coronation in 1902. These were distributed at large dinners for 500,000 people given in London by the King on 24 June, in advance of his coronation. It is a precious reminder that my ancestors were in London that day.

Mug distributed in London to commemorate the coronation of 1902.

In advance of the next coronation, that of King George V and Queen Mary in June 1911, there was a massive ‘Coronation Exhibition’ at Shepherd’s Bush in West London. My great-grandfather, Charles William Dixon (a resident of Glenroy Street, Shepherd's Bush, at the time), was recorded in the census of April as an electrician with the pencil annotation ‘Exhibition’, doubtless referring to his work for the upcoming Coronation Exhibition, which opened in May. It seems that he had also worked on the Olympic Games held at nearby White City in 1908, which was opened by Edward VII.

With the coronation of 1937, the amount of memorabilia surviving becomes larger, as I have a commemorative plate and programme from the event. This was the first coronation to be filmed, allowing people beyond London to experience it for the first time. It seems likely that my ancestors saw footage of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth being crowned on cinema newsreels. The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 was the first to be televised. My great-grandmother, Edith Dickinson, bought a television specially to watch the event.

Edith came from a mining family in County Durham and had married a coal miner, William Herbert Jefferson. She was clearly determined to watch the event in her terraced house near Sunderland. I have a mug belonging to my maternal grandmother that marks the occasion. Her husband was my grandfather, the Rev. William Herbert Jefferson (son of Edith), who was appointed to the vicarage of Belmont by the Queen in May 1972, a few days after Edith’s death. My grandfather had arranged for his church at Lamesley to be floodlit for the 1953 coronation.

Edith Jefferson, née Dickinson (1892-1972).

And so I come to this month’s coronation, for which I now also have memorabilia to add to my collection. Like my great-grandmother in 1953, I watched it on television. But I was also fortunate enough to visit Westminster Abbey on the following Monday, having recalled from my research that in 1838 the public was allowed to see it as was set out for the ceremony and wondered whether this opportunity might also occur in 2023. It was amazing to see the coronation chair in place and the ornate screen made for the King's anointing. And last week, at Lambeth Palace Library, I saw the bible with which the King was presented.

When I contemplate the varied and subtle ways in which my family’s experiences have been intertwined with those of the Royal Family, I am filled with fascination. There is something wondrous about such continuity, like the coronation itself. It is a valuable inheritance.